“Marielle showed us it is possible”

After the assassination that shocked Brazil, a wave of Black, queer women are running for election

By Mariana Fagundes

Only have a minute to read this newsletter? Here it is in brief:

🗳️ Brazil votes in general elections on October 2, and the legacy of one slain councilwoman looms large over the political scene.

🇧🇷 Marielle Franco was a Black, bisexual woman from the favela, who represented some of the most marginalised people in the country on the Rio di Janeiro city council.

✊🏾 Since her murder in 2018, scores of women of colour, queer people and those from low-income neighbourhoods have been inspired to run for office and counter the forces of the far-right in Brazil.

“I will not be interrupted!” These were the famous words of Brazilian politician Marielle Franco, speaking in a session of the Rio de Janeiro city council in March 2018. The man who had interrupted the city councillor did so to call for a return to military dictatorship in Brazil. Franco – a Black, bisexual woman from the favela – represented everything the former dictatorship had tried to suppress.

« I don’t put up with interruption from councillors of this house and I won’t put up with it from a citizen who comes here and doesn’t know how to listen to the position of an elected woman, » Franco said, turning to the audience as if giving a message to the entire country.

Days later, she was assassinated.

On the night of March 14, gunmen shot Franco dead in her car, also killing her driver, Anderson Gomes. She had just left a meeting on the role of Black women in Brazilian society. Her assassination remains unsolved and throughout the country, people continue to ask: who ordered the killing of Marielle Franco?

Though she was cut down in her prime, Franco has not been silenced. Her legacy has inspired a new generation of Black, queer and working-class women to run for office in Brazil. And as the country heads into a highly contested election between hard-right sitting president Jair Bolsonaro and left-wing former president, Lula da Silva, on October 2, her presence is felt more than ever.

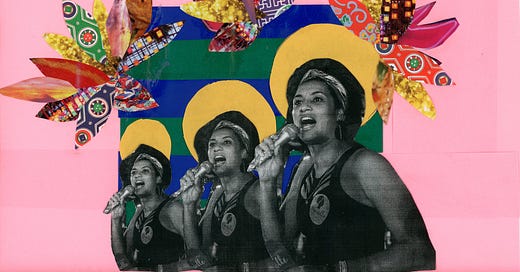

Collage by Mythili Sampathkumar

“Marielle’s voice remains in our ears, pushing us forward, telling us: ‘Don’t give up.’ And we don’t give up,” says Dani Monteiro, Franco’s former assistant who is now a Rio state deputy for PSOL, the same party as her late colleague. “There are no other Marielles. But there is a plethora of women – black and favela and LGBTQIA+ women – willing to fight for a reality we haven’t had until now.”

In the upcoming election, a record 33% of candidates are women, and 49% are Black. It is more difficult to analyse LGBTQIA+ participation due to significant data gaps. But NGO VoteLGBT+ has counted 304 self-declared queer candidates in the 2022 election so far – a figure they say is also a record high for the country. There have also been 36 requests to run under a “social name”, a practice generally used in Brazil by trans or non-binary applicants.

Dani Sanchez is running for federal deputy with PSOL, under the slogan « favela votes for favela ». For Sanchez, Franco represented the power of Black, queer and favela women, and highlighted their ability to overcome a shared history of subjugation due to structural racism, machismo and homophobia.

« I am inspired by Marielle to understand how my voice can go further and touch more hearts,” she told the Impact newsletter. “Black women move the community, now we want to move the National Congress. »

In 2020, the Marielle Franco Institute, set up by the councilwoman’s family following her death, launched the Marielle Franco Agenda: a set of anti-racist, feminist and LGBTQIA+ commitments inspired by the political convictions of its namesake. In the municipal elections of 2020, more than 700 candidates from 300 municipalities in Brazil committed to the proposal. Of these, 81 were elected councillors, mayors and deputy mayors in their municipalities.

Image courtesy of Dani Sanchez

could be more challenging for supporters of the agenda. Data collected by the institute shows that while Black women are the largest demographic group in Brazil, comprising over 25% of the population, they currently represent under 2% of seats in the National Congress.

Political scientist Letícia Medeiros founded the NGO Elas no Poder (women in power), which campaigns to increase the participation of women in politics. She says that, compared to municipal elections when mayors, deputy mayors and city councillors like Franco are chosen, general elections for deputies, senators, governors and president are more expensive and more difficult to win for marginalised candidates.

The fact that candidates are required to campaign in different cities in a general election presents significant financial obstacles. Added to this is the growing threat from the far-right. Bolsonaro’s presidency has seen an increase of hate speech and the spectre of political

violence.

“Disputes around the presidential candidacies have made the political debate violent, which mainly affects women who are on the streets defending their flags and their causes,” Medeiros says.

Image courtesy of Dani Monteiro

Beyond the halls of power, Marielle Franco’s presence is still felt within the community she represented. In July this year, on the day she would have turned 43, a statue in her honour was unveiled in Rio de Janeiro, in the same square where she would go every Friday to give an account of her performance as a councillor to her constituents.

“It is a message to those who think they will be able to erase and interrupt the memory of Marielle. Not only will we not allow her trajectory and her struggles to be forgotten, but we will continue to multiply initiatives in her honour,” says journalist Anielle Franco, the executive director of the Marielle Franco Institute and Franco’s sister.

The slain councilwoman is honoured far beyond Brazil – her colleagues at PSOL say there are now more than 150 different streets, parks and other public places around the world named after her, including the Marielle Franco garden in Paris.

Asked what her sister’s legacy should mean for women voters in Brazil and around the world, Anielle Franco says: “Never forget that we can occupy all the spaces in society that we want. Take care of each other. Try to know and multiply the stories of non-white women who live another experience of being a woman.”

Marielle Franco’s supporters often invoke a proverb when describing her legacy: “They tried to bury us, they didn’t know we were seeds”. In the upcoming election, it has become a rallying cry for the candidates following in her footsteps. They are nicknamed the “seeds of Marielle.”

It’s a sentiment they want to take from the ballot box to the halls of power.

“Marielle showed us it is possible.” Monteiro says. “I know it is possible.”

— Mariana Fagundes is a Brazilian journalist. She is also a PhD student at the University of Brasilia and the University of Rennes 1, researching feminist media and activism.

— Mythili Sampathkumar is

an independent journalist based in New York.