Young women are leading Pakistan’s recovery from climate disaster

Meet the volunteers working to rebuild their communities

Welcome to the Impact newsletter, a weekly dispatch of feminist journalism from around the world. This week, Amel Ghani reports from Pakistan on how young women have led the way in the recovery from the most devastating floods in the country’s history, and how they’re coping one year on.

By Amel Ghani

Last summer, eighteen-year-old Maryam Jamali sat in her village in the west of Pakistan and watched the flood waters rise. In previous monsoon seasons, the water would regularly bypass Killa Saifullah; but this was no ordinary year. The floods that hit Pakistan in 2022 would be the worst in the country’s history.

“I had this feeling of dread that given the amount of rain, we would be flooded. I brought it up with my parents and others but was told to stop talking about it as it would be a bad omen,” Jamali says.

Her fears came true in just a few days when, after six hours of continuous rain, the waters started rising in Killa Saifullah. At the time, government aid was barely available in the already flooded areas, let alone Jamali’s small village in the province of Balochistan.

Jamali and her family worked to try to help other families stuck in their homes as water levels rose. She says her intimate knowledge of her own community helped her target relief to those who needed it most. She knew, for example, which households were run by widows, who were unable to stand in long public lines to receive aid due to local customs which dictate that it would not be appropriate for women to stand alongside men in public spaces.

“My family and I decided to help people wherever we could, at least until government help arrived,” she said. They soon realised no help was coming.

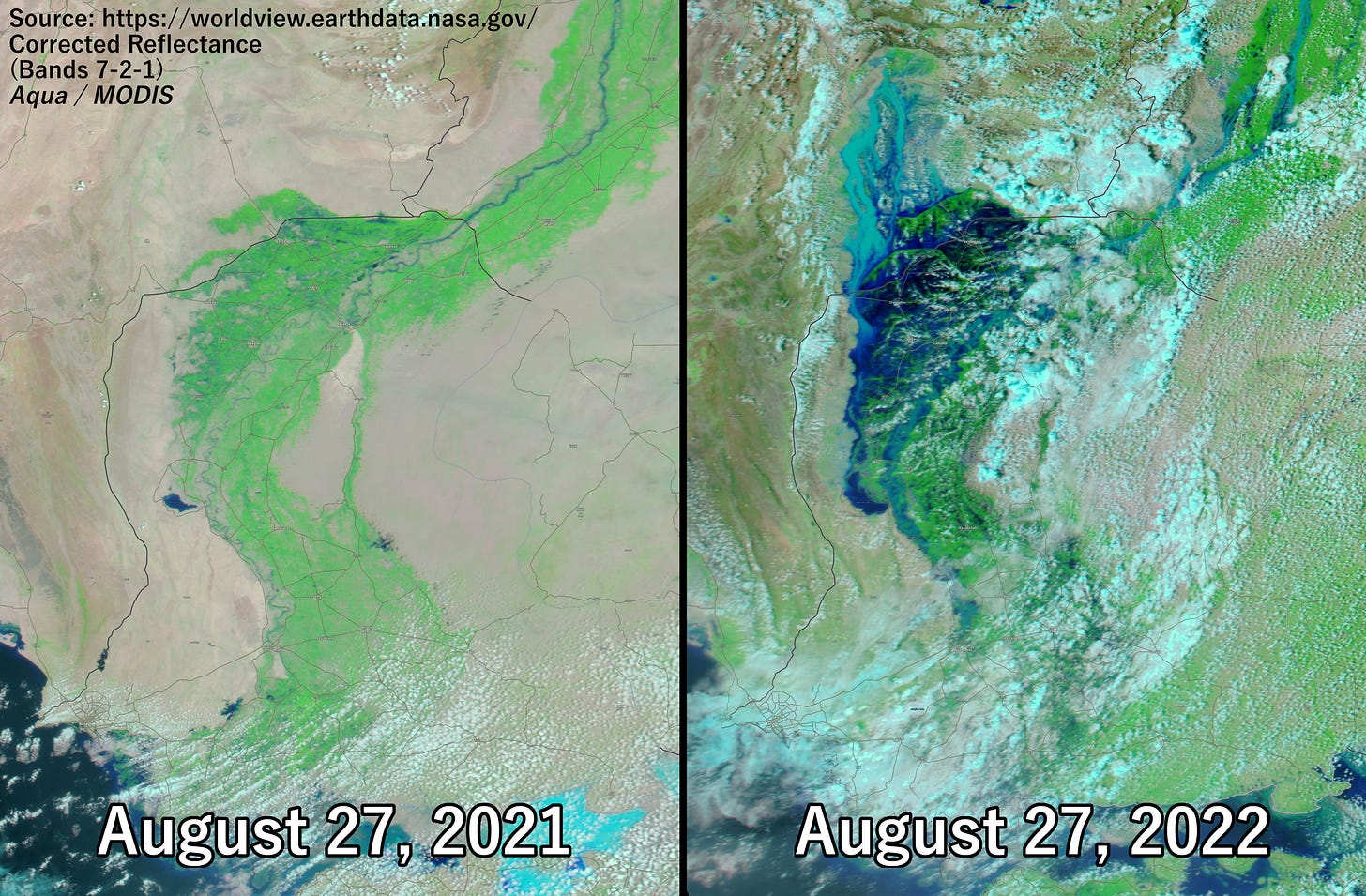

The 2022 floods, which swept Pakistan from June to August, were a climate catastrophe of immense proportions, the scale of which can be difficult to grasp: one-tenth of the country was inundated, with some 75,000 square kilometres submerged at the peak. Driven by a rapidly warming Indian Ocean, back-to-back heatwaves and melting glaciers, the monsoon rains were relentless. The province of Sindh received 726% more rain than average in August, while neighbouring Balochistan experienced increased rainfall of 590%. The resulting devastation affected more than 33 million people, killing 1,700 and displacing more than two million. But the floods have also galvanised new movements in Pakistan to combat the gendered effects of climate disasters.

Lacking help from the government, Jamali turned to Twitter, posting pictures of her flooded village and asking for help to do more than her family could manage by itself, as the number of people affected by the floods increased with each passing day. One of the groups who responded to her call for support was Mahwari Justice, a period poverty initiative set up as waters were rising around the country.

When Mahwari Justice co-founder Bushra Mahnoor was ten years old, she watched a girl her age walking in her hometown after a flood, her clothes stained with blood. Twelve years later, Mansoor, by then a psychology student in Lahore, knew there would be millions of girls in the same predicament – left with no way of managing their periods amid the wreckage.

Soon, she began to hear disturbing stories from the flooded areas like Jamali’s hometown. “A friend told me about how in Lasbela, in one relief camp two sisters were washing and sharing the same rag during their periods,” Mahnoor says. “There was a sense of urgency about it.”

Mahnoor consulted friends, found a partner in architecture student Anum Khalid, and started to raise awareness about menstruation via a Twitter account. The students also launched a GoFundMe page, raising more than €40,000 for menstrual relief on the ground in flood-affected areas.

One year since the flooding began, Mahnoor says Mahwari Justice has successfully helped more than 100,000 menstruating women in the affected areas and have put the issue of period poverty on the map in Pakistan. They did so thanks to the many volunteers they worked with in flood-hit regions.

At the beginning, the activists provided women with traditional commercial pads and hygiene kits containing soap, washing detergent and underwear. As they did more research and received feedback from women and volunteers in the field, they began to adapt the kits to the areas they were sending them to, depending on the products that women and girls there were familiar with and able to use more comfortably under the circumstances. This included adding pieces of cloth and pieces of string, something some traditionally use during their period.

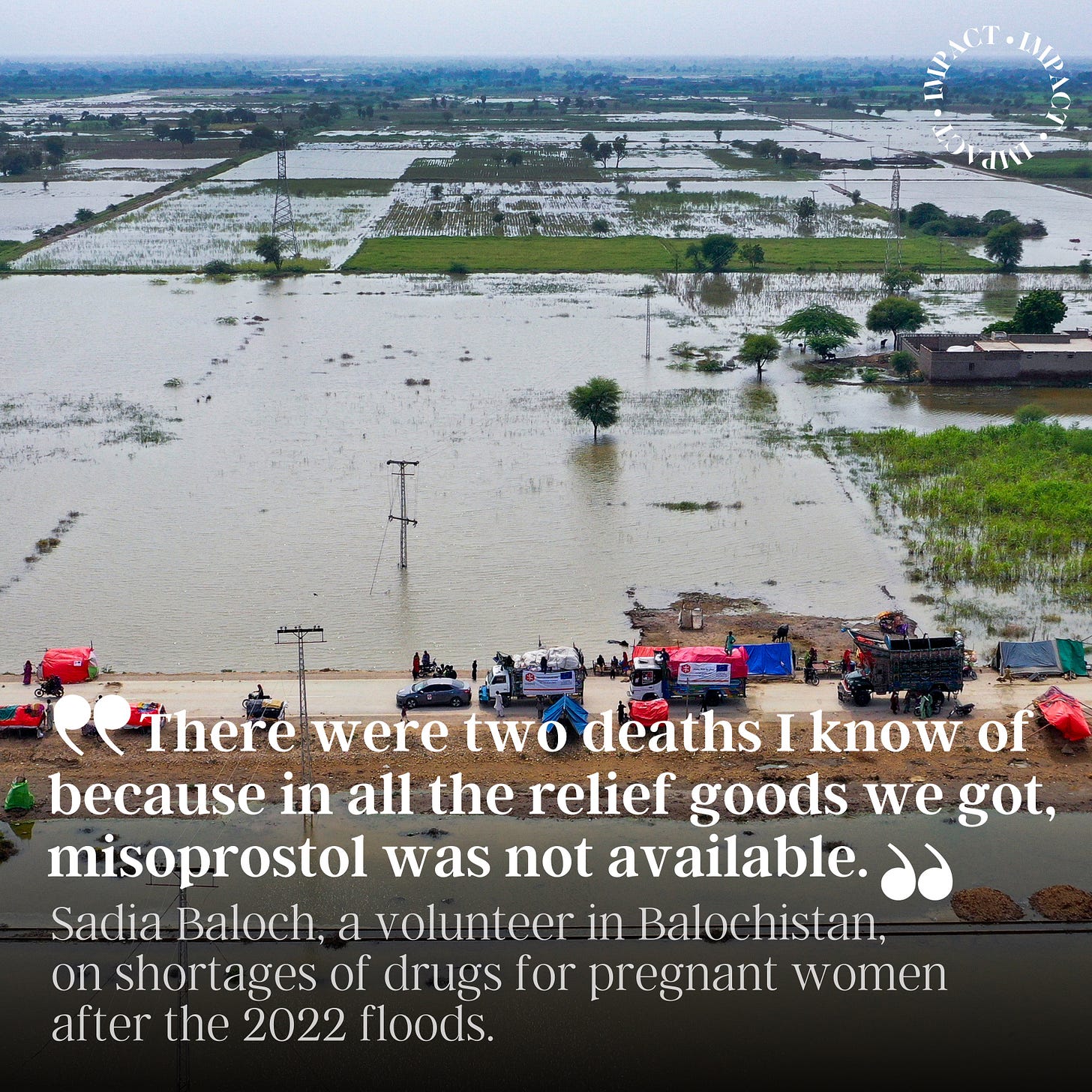

Midwives also rallied to provide healthcare to women and girls following the disaster. In September 2022, UNFPA estimated that nearly 130,000 pregnant women in Pakistan were in need of urgent health services. While relief organisations relied on midwives to reach communities and ensure safe deliveries during the time, activists say that many communities were overlooked due to the sheer scale of the floods.

“Midwives are an essential part of communities here. They stay with women and care for them for the first few days after they give birth,” says 23 year-old Sadia Baloch, another independent volunteer, who was providing relief in her town of Jhal Magsi. She gives the example of a local midwife who went to all the displacement camps herself to provide care. “This woman knew the women and not only helped with deliveries but also knew how to explain vaginal infections like UTIs to women there and offer treatment,” she says.

Parlez-vous français ? Impact is also available in French:

Baloch says there was already a huge disparity in the healthcare provided to women compared to men in her region, and this was only exacerbated during the floods. In that context, drug shortages could prove as deadly as the environmental disaster itself. Misoprostol is used all over the world to stem excessive bleeding after childbirth and to induce labour. It is also used as part of a medication abortion. But it was in short supply in Balochistan.

“There were two deaths I know of because in all the relief goods we got, misoprostol was not available. The local midwife knew of the medicine, she knew how to use it and asked for it but because it wasn’t available, she wasn’t able to use it,” Baloch says.

It was a similar story in Killa Saifullah. “Their health has been compromised a lot,” Jamali says of the pregnant women in her village. “A lot of them didn't receive the pre- and postpartum care they needed.”

Today, Jamali is far from the hopeful teenager advocating for her community she was in the summer of 2022. “I've realised no matter what I do, I cannot compensate for government failure,” she says.

She says that while the floods are no longer a major part of public discourse in Pakistan, people in her region are still suffering. She feels political leaders have forgotten the disaster, and now only mention the floods only to engage in political point scoring during international forums.

But Jamali has not forgotten. She is still working to ensure the long-term response to the floods does not leave women and girls behind. Many people remain unhoused after their homes were destroyed in areas that stayed submerged for months after the floods. “It impacts women more because of the need for privacy,” she says. For many women, especially within the flood-hit areas in Balochistan, being out in public within the view of men they don't know goes against traditional norms. Women in the open are also at greater risk of abuse in a crisis situation.

With this in mind, Jamali, now all of nineteen years old, has shifted her efforts to building shelters for her neighbours.

— Amel Ghani is a freelance journalist based in Lahore, Pakistan. She writes about real estate, the environment and various human rights issues.

— Mythili Sampathkumar is an independent journalist based in New York.

Want to support the Impact newsletter? Check out the Les Glorieuses online shop and buy a notebook or gift bag!